About Me

Honestly, it feels very weird to have my own website. As the stereotypical youngest child, I love attention, but I can't help but despise advertising myself for the whole world to see. Perhaps that's a midwest thing? Or maybe the fact that I'm secretly 80-years-old. Who's to say?

I was born and raised in Omaha, NE, and graduated from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in May 2021. I'm the youngest of four and all of us were born in a five year period. I did what I could to stand out among my siblings but somehow ended up enjoying the same activities they did, such as newspaper. I actually come from a family of journalists, but I never thought I'd actually be a journalist until I wrote my first story. I was instantly hooked.

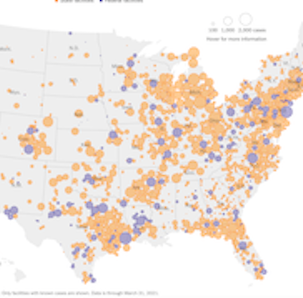

Still, my mom insisted I put my "math brain" to good use. So, I entered the world of data journalism with the help of my colleagues at Climate Change Nebraska, The New York Times, The Salt Lake Tribune and The Dow Jones News Fund. In 2021, I was part of The New York Times' Pulitzer Prize winning team that collected data related to COVID-19 cases across the U.S. — including the incarcerated population.

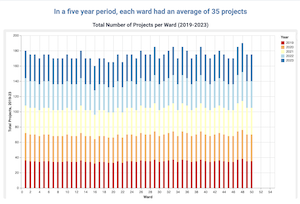

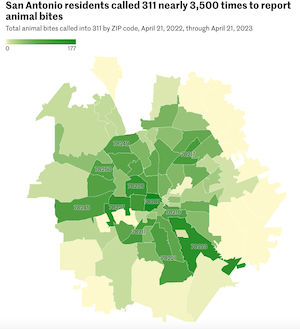

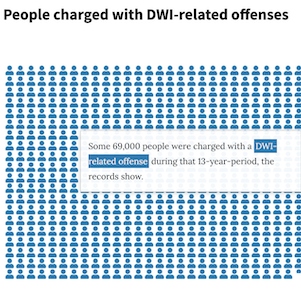

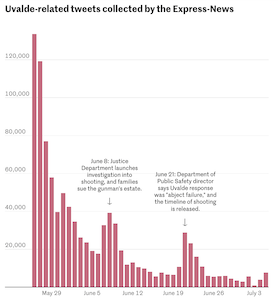

Between July 2021 and January 2024, I served as the data reporter at the San Antonio Express-News via the Texas Development Hub, and I then worked at the Flatwater Free Press as their first election guide editor. I'm currently a UChicago graduate student studying Computational Analysis and Public Policy. I will graduate in June 2026. Explore my data-related journalism endeavors below.